Museum of the Origins of Man

OF SKULLS AND MEN: INTERPRETING THE ANTHROPOMORPHIC SCULPTURE OF THE LOWER AND MIDDLE PALEOLITHIC

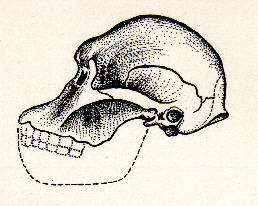

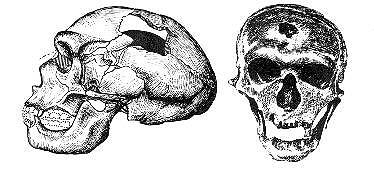

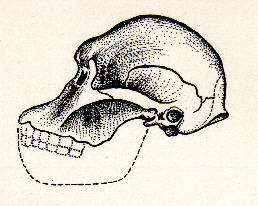

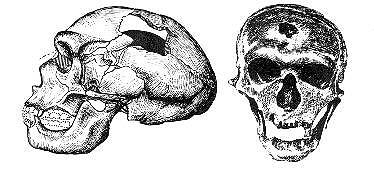

Fig. 3.1) Australopithecus gracilis (africanus).

Side view drawing. This hominid is very similar to Homo habilis.

This skull has affinities with the Oldowan anthropomorphic sculpture of S. Severo (Fig. 4.1).

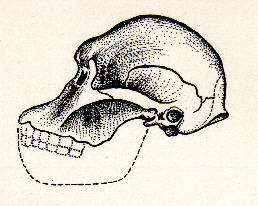

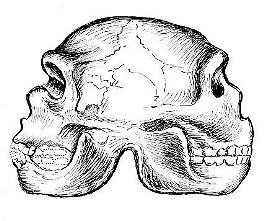

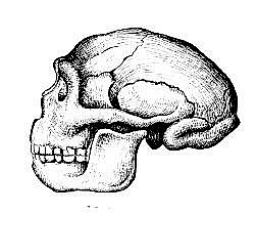

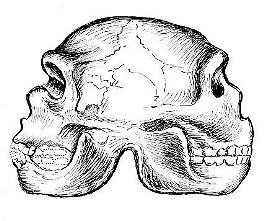

Fig. 3.2) Homo erectus (Sinanthropus).

Drawing of the skull reconstructed by F. Weidenreich with several fragments of skulls, both male and female, of various ages. Through this skull, in lateral profile, we can interpret the sculptures of human heads without chin and forehead of the Acheulean and the Clactonian.

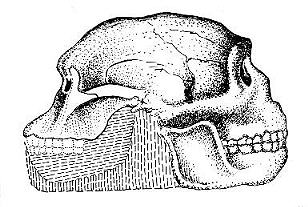

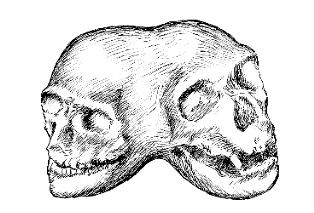

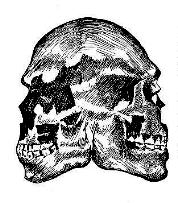

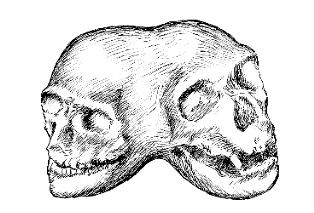

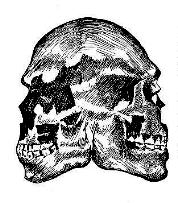

Fig. 3.3) Graphic simulation of the union of two skulls of hominids that lived at the same time. This parameter can be used to interpret the bicephalic anthropomorphic sculptures of the lower Paleolithic. [Drawing by P. Gaietto, 1982.]

On the left is Australopithecus africanus, on the right Homo erectus (Sinanthropus). The dots with vertical lines refer to the sculptures that have no division between the jaws. Excluding vertical lines, the drawing refers to the sculptures in which the two mandibles are separated and join at the top.

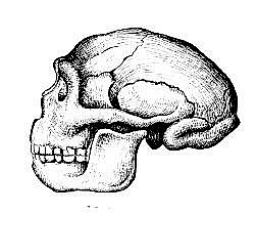

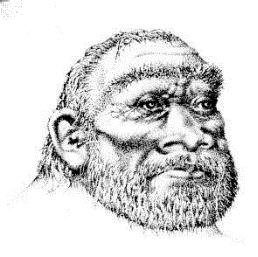

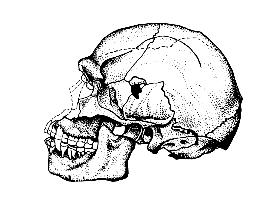

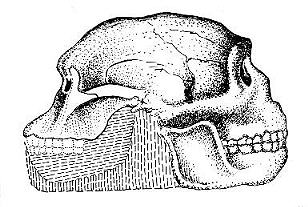

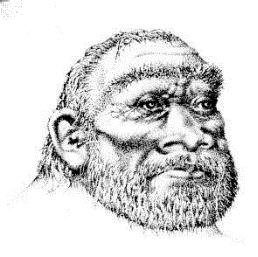

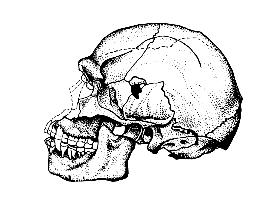

Fig. 3.4) Homo erectus with prominent jaw.

This human type does not appear in the skeletal finds from the Acheulean and the Clactonian, but it is found in the anthropomorphic sculpture. (See Fig. 4.3 - 4.4 - 4.5 - 4.6 - 4.7).

(Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974).

Fig. 3.5) Graphic simulation of the union of two skulls of hominids that lived at the same time, a useful parameter to interpret the bicephalic anthropomorphic sculptures in the final phase of the Lower Paleolithic. (Drawing by P. Gaietto, 1982.)

On the left, Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (the Old Man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints) and on the right,Homo erectus. For the representation of the skull of Homo erectus we used the reconstruction of the Sinanthropus, which was made many years ago by Weidenreich and deserves mention.

For the Acheulean and the Clactonian, that is for approximately 650,000 years (from 750,000 to 100,000 years ago) there has not been found a single complete skull of Homo erectus, only parts, and not even in the same place.

Recently a new type of hominid has been classified, known as Archaic Homo sapiens. Some remains of Homo erectus have been attributed to Archaic Homo sapiens, and there is no complete agreement between paleoanthropologists. No complete skull of Archaic Homo sapiens has been found. However, the differences between Homo erectus and Archaic Homo sapiens should be minimal and shouldn't influence the general profile of a head when interpreting a head represented in sculpture.

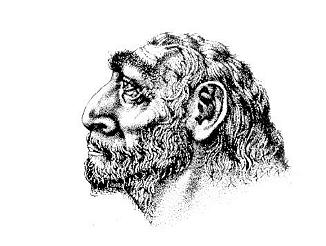

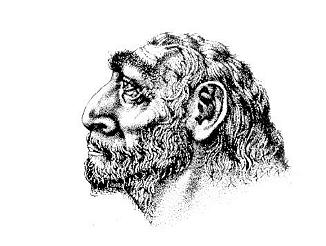

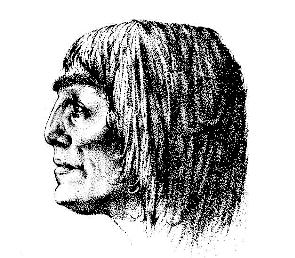

Fig. 3.6)Pre-Neanderthal woman.

(Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974).

Fig. 3.7) Pre-Neanderthal man.

(Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974).

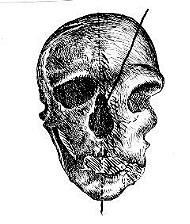

Fig. 3.8)Graphic simulation of two parts of the same skull of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (from La Chapelle-aux-Saints). To the left is the front view, to the right a profile view. (Drawing by P. Gaietto, 1982.)

This reconstruction was made in support of the bicephalic anthropomorphic sculpture found at Voltri (Genoa, Italy) (see Fig. 5.23).

NOTE: The drawings of the skulls, and also their combinations, have been introduced on this site in order to facilitate the interpretation of the anthropomorphic sculptures, which are representations of living "hominids", since in the Paleolithic, at least until today, no representations of skeletons have been found, neither in sculpture nor in painting.

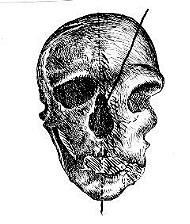

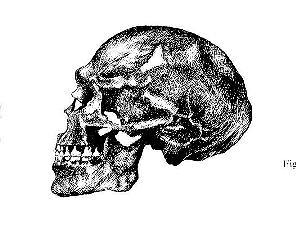

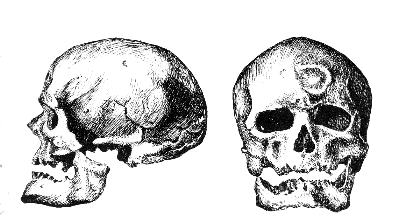

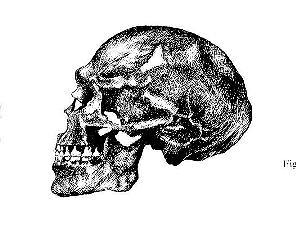

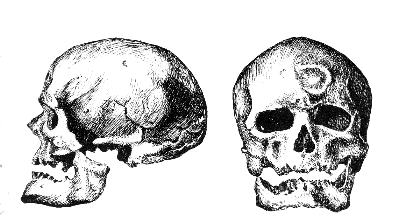

Fig. 3.9) Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (La Chapelle-aux-Saints).

Skull in lateral and front view, oriented in the orbital-auricular plane.

Fig. 3.10) Homo sapiens sapiens. (Predmost type, Moravia, Czech Republic.)

Skull in lateral view. He has the chin, but still the sloping forehead of the Neanderthals.

This human type is more frequently found in anthropomorphic sculpture of the Upper Paleolithic than the Cro-Magnon (Fig. 3.16).

Fig. 3.11) Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Skhul Cave, Israel.)

One of the most modern Neanderthals and it finds confirmation in the sculpture found at Balzi Rossi (Liguria, Italy) (Fig. 5.32), that represents the head of a Neanderthal woman (left side) wearing a beautiful hairstyle.

Fig. 3.12) Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (the Old Man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints).

The position of the skull in semi-frontal view is related to the sculptures of Neanderthal (Fig. 4.19 and 5.24).

Fig. 3.13) Homo sapiens sapiens (Cro-Magnon type).

Semi-frontal view. In this position the heads represented in sculpture seem to show the absence of forehead of the Neanderthals, while the Cro-Magnon has the forehead of a modern human (Fig. 3.16). Also the chin seems longer and is so represented in sculpture (Fig. 5.24 - head left side).

Fig. 3.14) Graphic simulation of the union of two skulls. On the left, Homo sapiens sapiens (Cro-Magnon type), on the right Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (La Chapelle-aux-Saints). The skulls are in semi-frontal position.

This simulation refers to the bicephalic anthropomorphic sculpture found at Campoligure (Liguria, Italy).(Fig. 5.24) (Drawing by P. Gaietto, 1982.)

Fig. 3.15) Graphic simulation of the union of two skulls. On the left is a modern Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Skhul V) (Fig. 3,11),on the right a Homo sapiens sapiens (Predmost type) (Fig. 3.10).

This type of combination is frequent in sculpture. (Drawing by P. Gaietto, 1982.)

Fig. 3.16) Homo sapiens sapiens (Cro-Magnon type).

See the sculpture from the Balzi Rossi cave (Fig. 5.32) in which the skull and the human head (right side) have the same jaw with chin, the same forehead, and the same skull cap, and a slight difference in the nose. (See also Fig. 5.35).

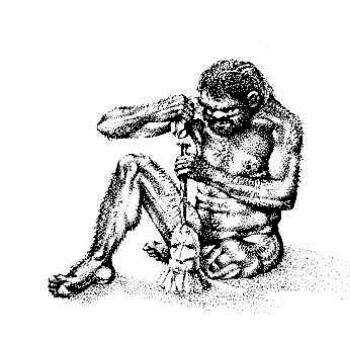

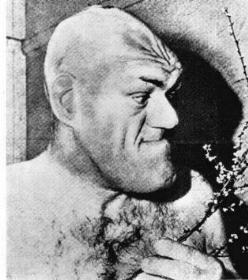

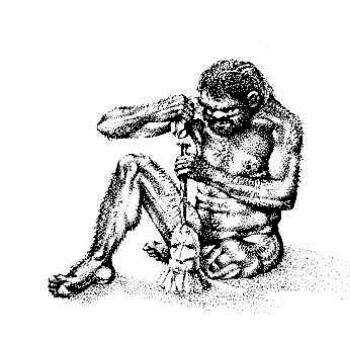

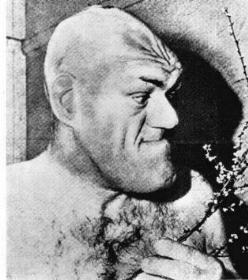

Fig. 3.17) Homo erectus "sculptor".

The stone working technique used to produce sculptures was more complex than that used for the production of tools.

The processing for the production of stone tools consisted of the removal of flakes that must be sharp or pointed. The production of sculptures was similar to that of external modeling of tools, in which wood or bone strikers were also used to avoid breaking the stone, while removing flakes to shape it, and where only one hand was used to strike.

For the inner modeling of the sculpture – that is for making hollows by removing stone fragments from below the surface – it was necessary to use a chisel of wood or bone, and a flint, and two hands were necessary as in this drawing. This double technique is well seen in the sculpture found at Maribo (Fig. 5.17) (Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974.)

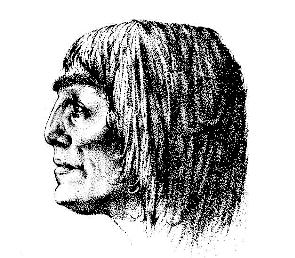

Fig. 3.18) Homo sapiens sapiens.

Image of woman found in sculptures of the final Middle Paleolithic. (Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974.)

Fig. 3.19) Homo sapiens sapiens.

Image taken from sculptures of the final Middle Paleolithic. (Drawing by A. Cestino on P. Gaietto's directions, 1974.)

Fig. 3.20) Man with acromegaly, showing a disease that deforms the head.

We wanted to put this subject in relation to some human types represented in sculpture (seeFig. 4.12 - 4.21 - 5.39- 5.40). The resemblance is extraordinary, and that is why we wanted to make this observation, useful for future research.

Fig. 3.21) Hairstyle from African ethnography.

In the sculptures of heads of the final phase of the Middle Paleolithic and in the "Venuses" of the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, pointed heads are frequently found that can be hoods or hairstyles.

Fig. 3.22) Homo sapiens sapiens. From the burial found at Arene Candide, Finale Ligure, Italy.

The headdress of sea shells has some affinities with representations of heads from the Upper Paleolithic, among them the famous Venus of Willendorf (Fig. 8.6).

Archaeological Museum of Genoa, Pegli (Italy).

Fig. 3.23) Girl with skull of a deceased relative. African ethnography.

This use, perhaps, finds a correspondence in the sculpture found at Tiglieto (Liguria, Italy) (Fig. 8.2), that represents a Neanderthal with the head applied to the back.

Fig. 3,24) Trophy skull of a head-hunter of Borneo.

In ethnography the skull can be linked to the rite of the enemy defeated in battle, as well as to the cult of the deceased relative.

A cult of deceased relatives has been hypothesized for the Lower Paleolithic since so many skull fragments have been found. In the Paleolithic, a cult linked to the head is indubitable because most of the sculptures represent heads.

During the Paleolithic, hanging sculptures were made which were suspended like this skull (see Fig. 7.6,1 and Fig. 7.12).

NEXT

Index

HOME PAGE

Page translated from Italian into English by Paris Alexander Walker.

Copyright©2020 by Museum of the Origins of the Man, all rights reserved.